Since the launch of the unique ID in this Maharashtra district, the 12-digit identity has been inextricably tied to people’s lives — from a mother without Aadhaar who was denied a maternity benefit to a child who is out of school, to officials who say it has streamlined benefits. What does the recent Supreme Court judgment mean for their lives?

Aadhaar nahin, toh niradhaar (Without Aadhaar, there is no foundation),” says Raju Narayan Thakre, father of Tembhli village sarpanch Azad Thakre.

Much before the Supreme Court started hearing a clutch of petitions challenging the Constitutional validity of Aadhaar and much before the unique identity number roiled a nation over concerns of privacy, Nandurbar had made peace with the 12-digit identification number.

Here in Nandurbar, a district in north-west Maharashtra that’s often counted among the most backward in the country, life continues to often come up against the Aadhaar test — at PDS shops, at the post office, in banks, schools and hospitals.

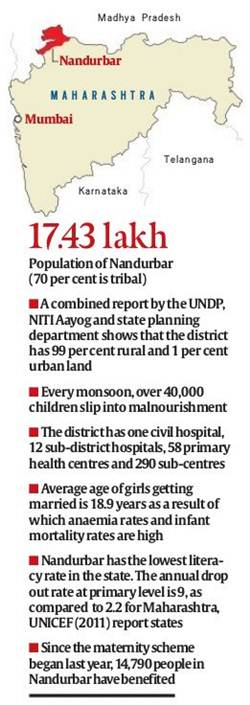

After all, Nandurbar was Aadhaar’s launch pad. It was here, in a small village of 1,600 people in Tembhli, that then prime minister Manmohan Singh and Congress president Sonia Gandhihanded out the first Aadhaar cards. That was 2010. Since then, according to data from the district collector’s office, 98.5 per cent of the district’s projected population of 17.43 lakh has got an Aadhaar.

On September 26, the Supreme Court, while upholding the Constitutional validity of the Aadhaar Act, upheld the linking of Aadhaar to allow people to avail of subsidies and benefits provided by the government, but struck down the requirement of linking the unique ID to bank accounts and mobile phone numbers or insisting on it for pension and school admissions.

With television a rare commodity in Nandurbar and literacy levels at a low 64 per cent (according to the 2011 Census), Collector Mallinath Kalshetty says the judgment will take time to reach villages deep inside the district. “Once the state government conveys (the order) to us, each department will sensitise people. We will follow the honourable Supreme Court’s order,” he says.

******

On the ground in Nandurbar, Aadhaar has worked in varying ways — to both include and exclude people, to empower and to delegitimise.

Maternity scheme

Some 15 km from Taloda town, down a mud road, is Jeevan Nagar, a village set up in 2003 for the rehabilitation of a thousand-odd villagers affected by the Sardar Sarovar dam project. The village of over 110 mud-splattered huts has electric poles, but is yet to be fully electrified.

Under a white LED bulb, with flies fluttering around, Jaura Vasave, 27, cradles six-month old Pratiksha, her first-born. She shares the house with 11 other people, two charpoys, a few trunks and a goat. Three men in the family do labour work, earning Rs 100 each a day.

At the mention of Aadhaar, she murmurs, “We don’t have money for that.”

Without Aadhaar, Jaura hasn’t got the Rs 5,000 that women are entitled to for their first delivery, under the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana, a maternity scheme that aims to provide nutrition to women and their new-borns.

Jaura says it was a local nurse who told her about the scheme three months ago. The nurse also told Jaura she would need a bank account to get the money. But when she went to a Taloda co-operative bank, the officials told her she would need Aadhaar to start a bank account. Then, she says, her husband Ranya, 25, skipped his day’s work, borrowed money from villagers and the couple made two trips to the Aadhaar centre in Taloda. Each trip, says Jaura, cost them Rs 400.

People continue to queue up at the Aadhaar centre in Shahada. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

People continue to queue up at the Aadhaar centre in Shahada. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

“The first time we went, there was no electricity for the biometrics, the second time, the finger printing failed because there was an injury on my hand,” Jaura laughs. “Aur kitni baar jaun, paise nahin hai ab (How many times do I go, there is no money left).”

Jayesh Khairnar, District Project Officer (DPO) of the Department of Information and Technology in Nandurbar, admits there have been glitches in the enrolment process. “The software version was changed by the UIDAI (Unique Identification Authority of India) and that led to technical issues. The new software had to be reinstalled and that took days,” he says.

But Jaura and her husband say they have given up. “We tried collecting money to visit the agent a third time but couldn’t get enough. So we decided we don’t want Aadhaar or the Rs 5,000,” says Ranya.